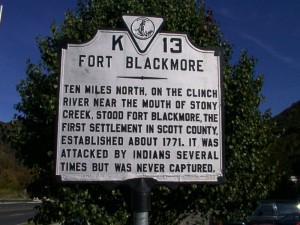

Lord Dunmore’s War-Fort Blackmore-Scott County, Virginia

Originally posted at http://www.danielboonetrail.com/historicalsites.php?id=85.

Written by Sally Kelly

The site of Fort Blackmore can be reached from Gate City, Virginia. At the Daniel Boone Wilderness Trail sign in front of the Scott County Courthouse, proceed East (right) on Jackson Street/Rt. 71. After approximately two miles, turn left onto Rt. 72, following signs for the present day community of Fort Blackmore. After about ten miles, you will cross over the Clinch River on a large bridge. Historical Fort Blackmore was on the north bank (far bank), to the left of the bridge. The site is on private property. At the north end of the bridge, on your left, is a monument erected by the DAR which tells about Daniel Boone and his connection with Fort Blackmore. To return to the Daniel Boone Wilderness Trail, turn around and retrace the route.

John Blackmore settled on land at the mouth of Stoney Creek on the Clinch River in 1773. He purchased 518 acres from the Loyal Land Company, and his acreage was surveyed on March 25, 1774 by Captain Daniel Smith, deputy surveyor for Fincastle County. At about the same time, surveys were entered for Isaac Crisman, John Thomas, Dale Carter, and John Blackmore, Jr. John Blackmore came to this area from Fauquier County, Virginia. At this time, Daniel Boone and his family had been living on land owned by David Gass, near Castle’s Woods, some dozen or more miles east; ever since Boone’s son James was killed by Indians as a party of settlers made its attempt to go to Kentucky in October, 1773. Young Boone, on that occasion, was traveling separate from the main party, in company with Henry Russell and others. Russell, son of Captain William Russell, “a Gentleman of Some distinction.” according to Royal Governor Lord Dunmore, was the organizer of that attempt, and Boone was the logician. After the murder, the immigration effort was aborted and some of the settlers returned to the Yadkin, and a few stayed on in the Clinch and Holston settlements.

In the aftermath of the murder of the boys, one of the survivors, one Isaac Crabtree killed an innocent Cherokee at a horse race near what is now Jonesborough, Tennessee. This event, and another brutal slaying by white frontiersmen of the nine members of the Mingo tribe on the Ohio in April of 1774 had stirred the tribes along the frontier into a war-like mood. Those few men taking up land on the Clinch were brave souls for many “families on the river had moved back to safety” according to surveyor Smith. Much of the detail that is known of Fort Blackmore comes from the correspondence of officers of the militia during the following months, in what became known as “Lord Dunmore’s War.”

The commanding officer of the Fincastle County Militia was Colonel William Preston, who resided near what is now Blacksburg, Virginia, on the New River. Officers reporting to him included Captain Russell on the Clinch; Major Arthur Campbell, Fort Shelby – at what is now Bristol; and Captain Daniel Smith, mentioned above. In a letter dated May 24, 1774, Colonel Andrew Lewis, of Augusta County, advised Preston that “Hostilities are actually commenced on the Ohio below Pittsburg.” In a War Council in June at the Lead Mines, near Fort Chiswell on the New River, it was decided to send militia under Colonel William Christian, Augusta County, to aid William Russell; and “at Preston’s instigation, William Russell sent Daniel Boone and Michael Stoner to tell John Floyd and other surveyors to come in from Kentucky. These two left for Kentucky on June 27, 1774.” This mission would first bring the previously obscure Boone’s name to widespread public attention.

It was a tense time among the scattered settlers along the Clinch River. On July 12, Colonel Christian wrote Preston that “four forts [are] erecting in Capt. Russell’s Company; one at Moore’s, four miles below this, another at Blackmore’s 16 Miles above this Place [Castle’s Wood] I am about to station 10 Men at Blackmore’s.” On the 13th, Captain Russell notified Preston “there are four families at John Blackmore’s near the mouth of Stoney Creek, that will never be able to stand it, without a Commd. Of Men, therefore request you, if you think it can be done, to Order them a supply sufficient to enable them to continue the small fortification they have erected.” Thus the fort took the name of the man on whose land it was built.

Captain James Thompson was the first officer put in command of the little fort. Men in the community were quite eager to join Lord Dunmore’s expedition to stop the Indians on the Ohio before they could come into the frontier settlements. Col. Preston had stated, “the plunder of the Country will be valluable. . . . it is said the Shawnese have a great Stock of Horses.” Those in command along the Clinch and Holston had difficulty manning the local forts with many eligible men wishing to go. On August 27, Daniel Boone returned from his mission to Kentucky; and almost immediately begged of Major Campbell to be sent on to Point Pleasant on the Ohio. Lord Dunmore had agreed to meet the forces from back country counties there with men he brought along from Tidewater. Boone set out, but was called back by Captain Russell to help defend the little Clinch River community as officer in command at Moore’s Fort.

On September 21, Captain Thompson went out with those Ohio-bound forces, and Captain David Looney was put in command at Blackmore’s Fort. On September 23 or 24, it was reported that “2 negroes [were] taken prisoner at Blackmore’s Fort, on waters of Clinch River, and a great many horses and cattle were shot down.” Captain Looney was absent, visiting his family on the Holston. Major Campbell wrote Col. Preston on the 29th that “Mr Boon is very diligent at Castle Woods and keeps up good Order. I have reason to believe they have lately been remiss at Blackmores, and the Spys there did not do their duty.” Two days later he wrote “Mr. Boone also informs me that the Indians has been frequently about Blackmores, since the Negroes was taken; And Capt. Looney has so few Men that he cannot venture to go in pursuit of them, having only eleven men.” On the sixth of October Campbell wrote to say that Indians had attacked at Shelby’s Fort without success; and the day after that, he said, was the attack at Fort Blackmore. An alarm of their presence was given by Dale Carter, crying “Murder, Murder!” Ensign John Anderson and John Carter ran out of the fort to help, but Dale Carter was killed and scalped; and the slaves were taken. After this, the people of the area were feeling that they needed a commander who lived on the Clinch. October 13, Captain Smith wrote Col. Preston that he had been shown a paper signed by inhabitants requesting the appointment of Daniel Boone to be Captain and take charge of the Clinch forts. Smith endorsed this request and stated “I do not know of any Objection that could be made to his character which would make you think him an improper person for that office.” Preston immediately promoted him.

Boone treasured his commission and carried it with him always until he was promoted again during the Revolution. Meanwhile, information was beginning to be received in these frontier parts that a battle had been fought at Point Pleasant on the Ohio between the forces of Colonel Andrews and the Indian tribes on October 10. Those forces met up with the Indians before they could join up with Lord Dunmore’s men, and fought a very successful engagement. Shortly thereafter, Dunmore negotiated a peace agreement ending the hostilities at Camp Charlotte. Some portion of the Shawnee nation agreed to give up it hunting rights in Kentucky if settlers would remain below the Ohio River. Local militias were disbanded, and November 21, Daniel Boone was dismissed from his duties. The Cherokee now were the only force with which to be reckoned for the settlement of Kentucky.

Again, Daniel Boone would support a prominent man in a Kentucky settlement venture. Judge Richard Henderson of North Carolina, in late 1774, negotiated with Cherokee chiefs to purchase a large plot on land in Kentucky, irregardless that he could not do so legally; and that the Cherokee had no real claim to the land they sold to him either. He engaged Boone to go among the Cherokee during late 1774 to encourage them to meet at Sycamore Shoals on the Watauga in March, 1775, for the formal agreement and transfer of the goods that would pay for the purchase. Boone returned to the Clinch in early February and gathered some twenty men there to help him blaze the path through Cumberland Gap to the land Henderson wanted. Not all are known, they included Michael Stoner, David Gass, William Bush, and William Hays. It is not unlikely that this group included some of the men from the Fort Blackmore area. Squire Boone brought others from North Carolina and the combined band of trail blazers set out from John Anderson’s Blockhouse, on the North Fork of Holston, on March 10. Boone left the new Kentucky settlement, named Boonesborough in his honor, on June 13, 1775, enroute once more for the Clinch. “Boone set off for his family.” Henderson wrote in his journal. When Daniel arrived there, he found Rebecca about to give birth. In late July, she gave birth to a son, William, who did not survive.

In mid August, Boone and family, and a party of some 50 immigrants set off for Kentucky. Probably some of them were men from the Fort Blackmore area; and the party would certainly have passed the fort, perhaps stopping overnight, in their westward journey. This ends Boone’s association with Fort Blackmore. But the fort continued as a place of refuge for many more years. 1775 was a relatively peaceful year east of Cumberland Gap, but hostilities with the Cherokee came again in 1776. Warriors who did not agree with the chiefs who treated with Richard Henderson, led by one Dragging Canoe, began attacks along the frontier. And there were many Indian attacks in Kentucky that caused large numbers of immigrants to flee back over the Cumberlands to the Clinch, Holston, and Watauga settlements. One such Kentuckian, William Hickman, arrived at Fort Blackmore on the Clinch, where he found other refugees “sporting, dancing, and drinking whiskey in an attempt to forget their fears.” “Things could get pretty rancid.” he said, “after a long period of confinement in a row or two of smoky cabins, among dirty women and men with greased hunting shirts.” In June, two men were killed at the fort. And in September one Jennings and his slave met death at the hands of Indians.

Other forts had been erected along the Powell River, west towards Cumberland Gap, during 1775, including Priests, Mumps, and Martin’s. Col. Joseph Martin’s station was erected in January of that year, and he noted in his journal the stopover of the Henderson party of Kentucky settlers about the first of April. Col. Martin left in May to visit at his home in Virginia. Soon the people from Mump’s and Priest’s were driven out. When there were no more than ten left alive at Martin’s, those men fled to Fort Blackmore, where they found most of the people from the Mump’s and Priest’s forts. In July, 1776, Cherokees in force attacked at the fort at Sycamore Shoals on the Watuaga, and battled local militia at the Battle of Long Island Flats, near present Kingsport, Tennessee. About the same time, one Ambrose Fletcher, living near Fort Blackmore, had his wife and children killed and scalped. Colonel William Christian was again called upon by Col. Preston, this time to put down the Cherokee uprising. Jonathan Jennings of Fort Blackmore, and father of the Jennings who was killed, mentioned above, accompanied that expedition to the Cherokee towns on the Middle Tennessee River. After that, mention of Fort Blackmore in the known historical record becomes scanty.

There is one famous story, dating from 1777, that may or may not be true. Men in the fort heard a turkey gobbling. They wanted to go out hunting, but were prevented by a knowledgeable backwoodsman, one Matthew Gray. He convinced them that they were hearing Indians. He directed the men to create a distraction on the bank of the river, while he snuck across the Clinch. He was able to get where he could see the Indian warrior perched in a tree, making the turkey noises. Mr. Gray dispatched the “turkey” and fled back into the fort with the others. In 1779, John Blackmore and his family left the area to travel with the Donelson party, traveling by flatboat, to settle in middle Tennessee. Donelson mentions meeting up with the Blackmore group at the mouth of Clinch where it joins the Holston, so John Blackmore’s band must have gone down the Clinch by flatboat. Perhaps not all Blackmores left the Clinch – or possibly some came back – for they are mentioned again in April, 1790 in the journal of Methodist Bishop John Asbury. “We rode down to Blackmore’s Station, here the people have been forted on the north side of Clinch. Poor Blackmore had had a son and daughter killed by the Indians. They are of the opinion here that the Cherokees were the authors of this mischief.” Asbury goes on to say he had heard of two families being killed and of one woman being taken prisoner, but retaken by neighbors A few days later, the Bishop traveled on, noting that he “Crossed the Clinch about two miles below the fort. In passing along I saw the precipice from which Blackmore’s unhappy son leaped into the river after receiving the stroke of the tomahawk in his head . . . this happened on the 6th of April 1789.” Indian attacks on settlers along the Clinch, Holston, and Watuaga Rivers did not cease until after 1794, when a half breed, Benge, who had led many of the forays, was killed near what is now Big Stone Gap. Benge committed his last crimes near what is now Mendota, Virginia, on the North Fork of the Holston. He fled, with two captive women, over the Clinch Mountain, Copper Ridge, and, finally, High Knob Mountain before being caught up with.

This route probably took him very near Fort Blackmore. And so, it was right in the middle of Indian unrest from its beginning to its end. Just exactly when it was abandoned as a fort is not known. The land owner believes he is able to point out where the fort stood; but, for the most part, it has disappeared from sight. Its little cemetery is still findable, below the current highway bridge over the river, and to its right, near the bank of the river. Scott Countians who care for old cemeteries keep it cleaned and accessible. Many of its graves are unmarked.

Do you no the names of the 13 Long hunter Daniel Boone travel with

Hi Charles. Can you give me more details? Which trip do you mean?

Jeff Roberts

Doswell Rogers, William Roberts, and Elisha Wallen were living on the New River in Mont. Co. VA when the Battle of Point Pleasant took place. They were supposed to go with William Herbert to the Falls of the OH, but for some reason part of these men were reassigned to David Looney to go to the Clinch River area indtead and to build forts. Lt. David Crockett was in charge of building the forts on the Clinch. Therefore, these whose names are mentioned above did not take part in the Battle of Point Pleasant as some data states.

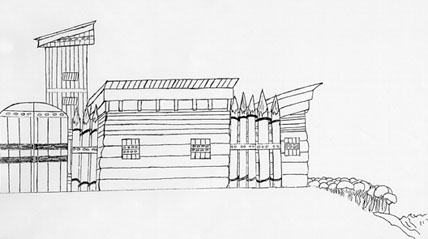

Could I use your sketch of the fort in an online article?

Hi JoAnne. It’s not mine. Please feel free to use it.